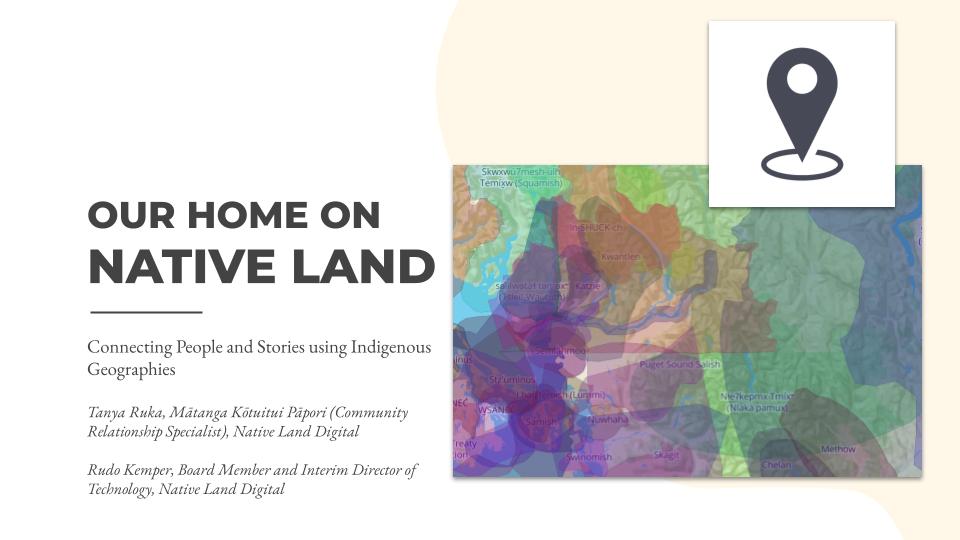

One of the most distinctive things about the Native Land maps are the borders. They overlap crazily and make a huge mess of colours. Nothing is very clean or neat or overly precise and it doesn’t look like a neat normal map.

That’s all on purpose, of course! Because in reality the polygons should overlap. Some of the maps I use as sources — in fact, most of those maps — get rid of the confusion of overlapping boundaries in favour of distinct, jigsaw puzzle-like areas. This approach, in my opinion, fits with a way of mapping that is quite deaf to the way Indigenous people and languages have moved and lived.

Nations

Indigenous groups around the world might be called tribes, nations, bands, and many other monikers. In any case, Indigenous identities don’t map (pardon the pun) precisely onto modern European notions of nationality and territory. As mapping technology advanced in Europe, the centrality of the border grew in Western culture. Colonialism lives and dies by the map — and the carved-up world is so central to our perspective that many of us today see the earth’s lands primarily as chunks of nations.

In the long, long Indigenous history of Turtle Island, a territorially strict approach to borders may have certainly been the case at times. Some large empires may have had defined boundaries, or natural features may have served as distinct borders; but there’s also a long history of borders defined more by language, seasonal travel, and landscape than by distinct lines. It’s diverse, and the “one nation per piece of dirt” model of mapping doesn’t hold up long.

There may also be lots of internal borders within nations, between family groups or more. I’ve heard it said that you know you’ve left your territory when you don’t know the names of the mountains or the plants anymore. Or that the boundaries, the extent of the land you live with — it’s just something you grow up knowing.

Overlapping

In an case, the reality is just that borders don’t always function the same as the simplified maps imply when it comes to indigenous history; there is a lot more movement, overlap, and complexity than one nation on each chunk of land.

From a mapping perspective, this is kind of a nightmare. Modern maps didn’t really evolve ways to show this kind of messiness when it comes to nations. There are plenty of very complex military or demographic maps out there, but most people aren’t used to seeing nations overlapping — unless they’re at war or something.

The alternative to allowing territories to overlap would have been to put myself in the position of deciding whose territorial claims are valid as opposed to others. I would have had to come up with a strategy to align borders and deal with the reality that some areas were used by more than one nation at different times of the year. Too tough and too much responsibility!

Overlapping allows people to get a sense of the depth and complexity of Indigenous history where they live, and since the map is also mostly ahistorical, it allows people to investigate some changes over time as well.

Exceptions

There are some exceptions for the overlapping maps — treaties. Well, mostly. In fact, treaties also have exceptions, where sometimes treaty lands mapped over the same area multiple times. Sometimes this was due to bad mapping, rough estimates of territory, or just plain broken treaties that had to be rebuilt over and over.

A note about government treaties — these were virtually never delineated by coordinates, but rather by landmarks. Here’s an example:

… thence by the eastern and northern shores of Lake Manitoba to the mouth of the Waterhen River; thence by the eastern and northern shores of said river up stream to the northernmost extremity of a small lake known as Waterhen Lake; thence in a line due west to and across lake Winnepegosis; thence in a straight line to the most northerly waters forming the source of the Shell River; thence to a point west of the same two miles distant from the river… (see source)

When working with Tom Mitchell in Manitoba, and looking at the Treaty 1 & 2 boundaries, we realized that the Canadian government is somewhat off in the boundary they draw near Brandon. I didn’t believe it at first, but we had a good conversation about it… that I may write up another time.

Conclusion

I hope this all helps to make sense of why overlapping boundaries are so prominent in Native Land. Ultimately, I’d really like to explore ways of mapping that can, in print maps and online, handle overlapping boundaries in really elegant ways. People have suggested heatmaps, but that’s hard with polygons like this, especially when I want to preserve some detail.

I was in a museum the other day that had a map with plastic sliding overlays showing different territories and national borders over time. I liked that. I wonder what I could do with something like that…